Over the summer, a team of teachers with a shared interest in written and visual communication, research, and digital literacy attended the Future of Learning Institute at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. The biggest ideas of the week had to do with the kinds of learning our students most need in order to be successful in the future--ways of learning that build flexible, transferable thinking skills that they can use not only to complete current tasks but also to take on the complex and unanticipated problems, projects, and situations that they’ll face in our rapidly advancing world.

Students need to build content knowledge, but as they do so, they must develop a toolbox of intellectual skills that they can draw on even when they encounter drastically different information. Our students shouldn’t encounter the facts and ideas in our courses solely for the sake of knowing them; those facts and ideas should also be a vehicle for learning how to interact with, synthesize, and use information. As David Perkins tells us, we should not learn about the French Revolution so much as “think with the French Revolution to understand other conflicts or think with your ecological knowledge to revise some of your everyday behaviors.”

The great thing about the Future of Learning Institute was that it introduced us to a variety of well-conceived, research-based tools that can help us do this important work with our students. One of my favorite sessions, led by Mark Church of the Making Thinking Visible project, offered specific, simple, and powerful ways to build these flexible and transferable thinking skills. By offering and making students aware of thinking routines, we not only help them learn the material we’re teaching but also empower them to understand how their own minds are working. This thinking about thinking--metacognition--has repeatedly been identified as the key to deep learning that prepares students not only for our specific courses but also for the varied and much less constrained intellectual tasks they’ll face far beyond their school years.

In English 1, a course that is already built around scaffolded instruction in thinking skills, we have introduced two thinking routines so far. The first routine, “See, Think, Wonder,” builds students’ awareness of and facility with observation, including the important skill of looking closely at an object, image, or text without allowing inferences, opinions, or guesses to stand in place of fact. In this thinking routine, students view an image and separately record their observations (what they see), inferences (what they think), and questions or guesses (what they wonder). This seemingly simple thinking routine is actually quite challenging, since it requires students to distinguish between types of thinking that they may use interchangeably in everyday life. In many cases, students find that they tend to observe very little, leaping immediately to inferences and conclusions. The ability to slow down and observe closely is a vital first step not only in studying literature but also in participating in professional and civic life.

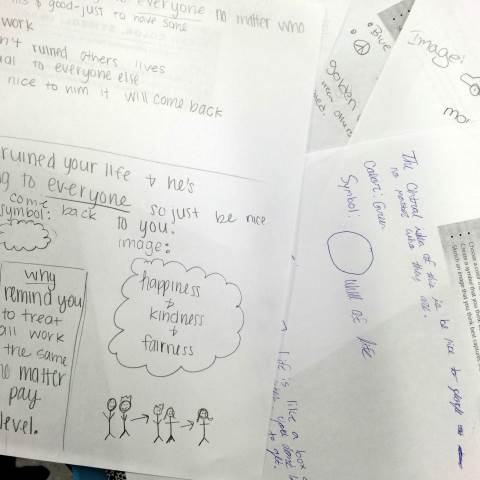

The second routine we’ve been working with is “Color, Symbol, Image,” or “CSI,” which helps our freshmen grasp and develop abstract ideas. At this age, our students’ development as abstract thinkers varies widely--some grasp concepts immediately, whereas others are more concrete. CSI has students read a passage or essay, consider what they think its central idea might be, and then select a color, a symbol, and an image that they feel represents that idea. As they think through and then explain why they selected as they did, they build their ability to move from concrete to abstract thought and then from visualizing to articulating their ideas. Because CSI separates cognitive tasks from one another, it supports student growth at many different stages of development.

The idea behind Making Thinking Visible is to use thinking routines repeatedly until students are adept not only at the routines but also at thinking about their own thinking--metacognition. For more information and resources on visible thinking, including many other routines, access the links below:

http://www.visiblethinkingpz.org

http://www.pz.harvard.edu/projects/visible-thinking

https://www.facebook.com/MakingThinkingVisible/

http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-047091551X.html

References

Perkins, David. Foreword. Making Thinking Visible. By Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011.